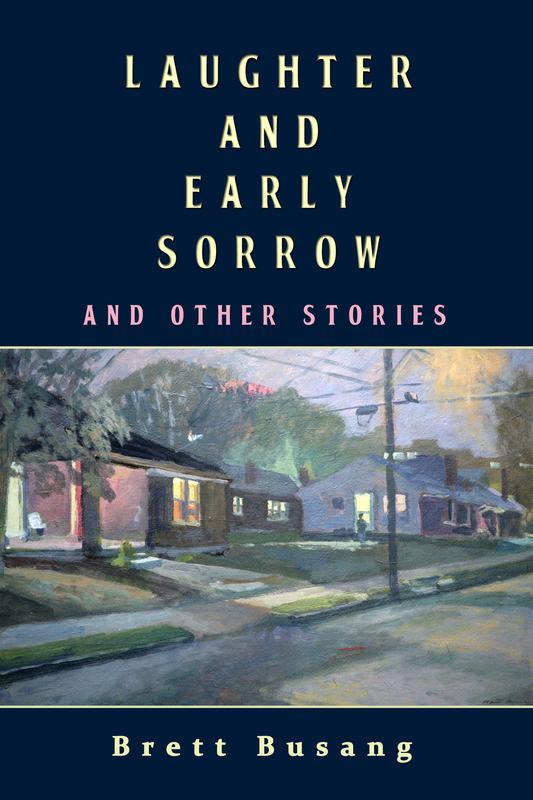

Laughter and Early Sorrow

by Brett Busang

Almost everybody who was born in the post-agrarian period separated by the two great wars grew up in a place whose growing pains were painfully obvious.

It was into such a place that my parents moved with my brother and me in tow. Our house was small, but serviceable; our neighbors forthcoming, but not so morbidly curious that they pried, and our world expanded in one way as it shrank in another. The sky was as blue as it is said to be in heaven. And we were so adrift in space and time that we became the terrestrial astronauts that so troubled Rod Serling that he had to write something about us each week for television.

Here the Main Streets of our grandparents were left to developers, who preferred parking lots to promenades. Here generously proportioned school buildings beckoned to a fertile population that would supply them so handily that, once a prototype was made, it could be endlessly reproduced. Here pastimes flourished as they never had before.

Here mostly white people settled in as Ricky Nelson serenaded them. Here needs were synonymous with desires. And here a culture that was made possible by the received wisdom of Father Coughlin, Leo Durocher, and Lawrence Welk sat back, adjusted its goggles, and proceeded, with limitations that grew with every sack of fertilizer that guaranteed a more perfect lawn, to have the time of its life.

It was here that I grew up and here (mostly) that I have roamed, from ball field to abbreviated living room to the topsy-turvy relations between hard reality and plausible delusion. I hope, in capturing some of its essence in prose, that the small underbellies which often lurk beneath the bigger ones become crudely, if only temporarily, visible.

Order

Laughter and Early Sorrow

by Brett Busang

Pay in USD

Order paperback

$15.95

plus shipping & handling

Pay in USD

Order eBook

$6.99